It snowed again this morning. On the 14th of April. Yesterday was so beautiful – the sky blue with a very few clouds occasionally blurring the warm sunshine – so waking up to the white stuff was a complete surprise. It didn’t last long and didn’t settle, but it was a reminder that our first winter in France has been unpredictable – in weather and in mood.

It is not the fault of Finistere; we knew we weren’t moving to a climate very different from the one we were leaving in the South West of England. It is about two degrees warmer here, and drier in summer, but the winters are wet and the skies leaden for days on end. Living so close to the forest we see both the benefit of this rain, and its disadvantages. The spring greens are just taking over from the brown, bare branches and we know that there will soon be a carpet of shiny green under our feet, and dry firm paths where now there is wet leaf mould and slippery mud. This is a fantastic place to live, and we have no regrets. But we now know why many here head for sunnier climes in January and February – it is a time to ‘tough it out’, rather than feed the soul, for me anyway.

My mood became very low, and I was unable to work at anything other than routine admin, of which I had plenty. The four books I have now been commissioned to write should have excited me, but instead weighed as heavily on my conscience as the clouds over the treetops, constantly threatening a deluge. I underestimated the difficult transition period needed after the change we had made. I worried about our grown-up children in the UK, was convinced I was physically ill because panic gave me symptoms and I became fearful of leaving the house. Masking depression and anxiety is hard work and that masking feels necessary when you don’t know the people around you very well (even though we have met some really lovely folk here) and are unsure of their response. I was, as the doctor here suggested, depressed about being depressed, furious with myself for not appreciating how lucky I am – always a dangerous place to go.

A friend from England saved me, in a way, by writing, on paper and sent in a real envelope, long letters two or three times a week, about day to day life, family things, normality (or what passes for it) and wise words. I am hopeless at replying to letters, but I wasn’t required to so I didn’t. What a relief. I can’t thank her enough, or those other friends who write and keep me in touch with the world. I felt a long way away.

There have been some wonderful times, when the sky has cleared for a few days, and the paths have had a chance to dry out sufficiently for me to look at something other than my feet as we walk, enabling me to look into the treetops, spotting long-tailed tit, wagtail, hearing the buzzards mewl and see them wheeling on open wings above the fir trees. There were snowdrops, and other wildflowers I didn’t recognise and days at the coast when the sun was warm on our faces even though it was March, and there was always Teddy the dog, and Peter, just sitting there with me.

And there is the thrush – mistle I think, rather than song – who started singing from February dawns (which are late here, an hour ahead of the UK) and who continues now, even as I write this in the early evening. He has favourite phrases, some almost nightingale pure and so loud you can focus on little else but his beauty, sitting proudly, as he does, on the topmost branches of the trees around the house. He may be three birds or more, but for me, it is one solitary companion lifting the heart, and the mood. He is marking his territory, impressing the lady thrushes, living his few short years on this earth to the height of his ability. And he speaks to my soul. I am writing this, and have made decisions about my workload and will now focus on writing and editing, as I have always wanted to do. The sound of the bird song reminds me there is so much more to living than the stuff the 21st-century calls ‘life’, and you can go days without spending more than a few euros here. So my mood is lifting, and once again I can see depression for what it is – an illness that comes and goes, like the weather. Spring is here, and soon we should get a warm settled spell.

And there is the thrush – mistle I think, rather than song – who started singing from February dawns (which are late here, an hour ahead of the UK) and who continues now, even as I write this in the early evening. He has favourite phrases, some almost nightingale pure and so loud you can focus on little else but his beauty, sitting proudly, as he does, on the topmost branches of the trees around the house. He may be three birds or more, but for me, it is one solitary companion lifting the heart, and the mood. He is marking his territory, impressing the lady thrushes, living his few short years on this earth to the height of his ability. And he speaks to my soul. I am writing this, and have made decisions about my workload and will now focus on writing and editing, as I have always wanted to do. The sound of the bird song reminds me there is so much more to living than the stuff the 21st-century calls ‘life’, and you can go days without spending more than a few euros here. So my mood is lifting, and once again I can see depression for what it is – an illness that comes and goes, like the weather. Spring is here, and soon we should get a warm settled spell.

I haven’t stopped reading poetry of course, and although I would love to find a reason to include some lines from John Keats’s ‘Ode to a Nightingale’ here, (rightfully one of the most famous love songs to nature, and a treatise on life, and death, and feeling and – well read it…), that would be to cheat Mr Thrush and the joy he has brought me recently. So instead here is Thomas Hardy, who could often reflect, gloomily, on the human condition and in this poem of the winter, of the turn of the year and a century (it was written in 1900) he meditates on what feels like a dark time, for him, for the world. Even as the song of the thrush intrudes upon such thoughts, he can’t be sure why the bird is so cheerful, or whether it is truly a sign of hope. The poem is more complex than I make it sound and reflects the scientific and religious developments of the 19th century and the conflict this caused many, but for me, at this moment, it is simply a tribute to the power of the smallest things to bring the greatest hope.

The Darkling Thrush

I leant upon a coppice gate

When Frost was spectre-grey,

And Winter’s dregs made desolate

The weakening eye of day.

The tangled bine-stems scored the sky

Like strings of broken lyres,

And all mankind that haunted nigh

Had sought their household fires.

The land’s sharp features seemed to be

The Century’s corpse outleant,

His crypt the cloudy canopy,

The wind his death-lament.

The ancient pulse of germ and birth

Was shrunken hard and dry,

And every spirit upon earth

Seemed fervourless as I.

At once a voice arose among

The bleak twigs overhead

In a full-hearted evensong

Of joy illimited;

An aged thrush, frail, gaunt, and small,

In blast-beruffled plume,

Had chosen thus to fling his soul

Upon the growing gloom.

So little cause for carolings

Of such ecstatic sound

Was written on terrestrial things

Afar or nigh around,

That I could think there trembled through

His happy good-night air

Some blessed Hope, whereof he knew

And I was unaware.

Thomas Hardy

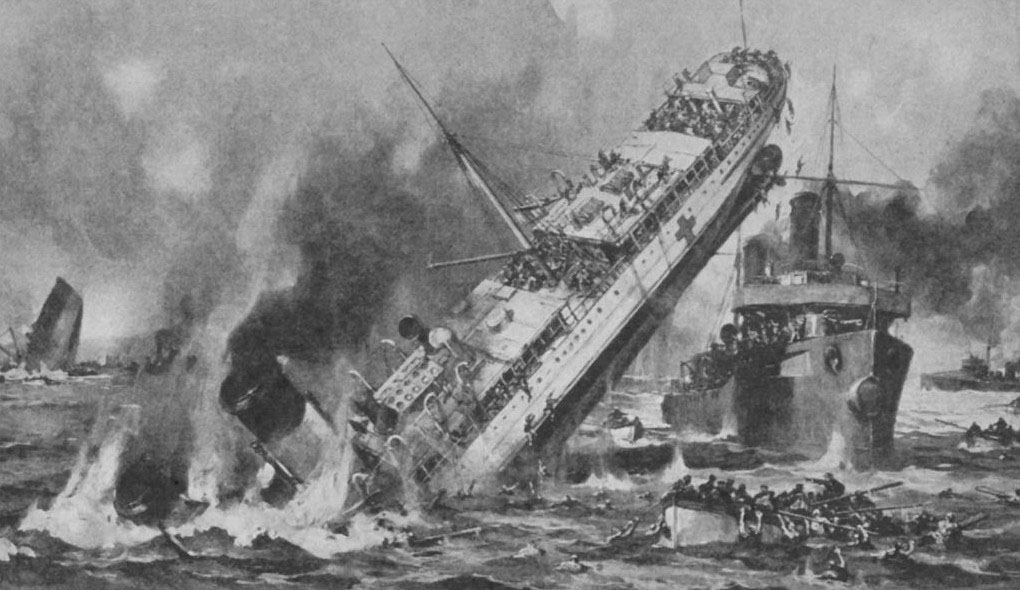

I wrote, before Christmas, of my concerns that post-Armistice Day centenary commemorations, the wonderful stories that are part of the heritage given to us by the Great War, would cease to interest the media. Despite there being much to learn from 1919 onwards, and the ongoing trauma experienced by soldiers and civilians alike, it does seem I might be right. Media stories of projects ongoing are thinning out and the Brexit horrors have overtaken almost every other subject in the news. So I have been determined to continue to run stories and examine themes from the Great War.

I wrote, before Christmas, of my concerns that post-Armistice Day centenary commemorations, the wonderful stories that are part of the heritage given to us by the Great War, would cease to interest the media. Despite there being much to learn from 1919 onwards, and the ongoing trauma experienced by soldiers and civilians alike, it does seem I might be right. Media stories of projects ongoing are thinning out and the Brexit horrors have overtaken almost every other subject in the news. So I have been determined to continue to run stories and examine themes from the Great War.

So – what to do with this amazing collection of letters, photographs, and even drawings, as well as the diaries and a costume? Even now I’m not sure, as I would be sorry to see it all disbanded and ending up in different places. I started by typing up the letters and diaries in order to share them with my cousins so that they would also know the

So – what to do with this amazing collection of letters, photographs, and even drawings, as well as the diaries and a costume? Even now I’m not sure, as I would be sorry to see it all disbanded and ending up in different places. I started by typing up the letters and diaries in order to share them with my cousins so that they would also know the

It is raining again, a fine misty rain that curls my hair and dampens everything, including my mood. I started this blog post before the additional chaos of a leadership challenge and more Brexit shenanigans, but also before the shooting in Strasbourg, a beautiful city in France, where we have recently settled. I realised this morning, as I sat gazing out into the forest, watching the slow tears of a wet Wednesday that it is harder than ever to see a real meaning in the Christmas holidays this year. In the UK, and in France, extremists on all sides are using politics as a vehicle to undermine fellow feeling, kindness and recognition that we are all inhabitants of one, enormous and very fragile planet. Nationalism rears up, obviously in riots and insidiously in parliament. We must take care of ourselves, and hold on to our values. Unless it seems, you are a Tory politician or a leading Labour member where the lines are blurred and everything is up for grabs. And as for Greg lake, well it was always an anti-Christmas song, and this year it seems we are definitely getting the Christmas we deserve.

It is raining again, a fine misty rain that curls my hair and dampens everything, including my mood. I started this blog post before the additional chaos of a leadership challenge and more Brexit shenanigans, but also before the shooting in Strasbourg, a beautiful city in France, where we have recently settled. I realised this morning, as I sat gazing out into the forest, watching the slow tears of a wet Wednesday that it is harder than ever to see a real meaning in the Christmas holidays this year. In the UK, and in France, extremists on all sides are using politics as a vehicle to undermine fellow feeling, kindness and recognition that we are all inhabitants of one, enormous and very fragile planet. Nationalism rears up, obviously in riots and insidiously in parliament. We must take care of ourselves, and hold on to our values. Unless it seems, you are a Tory politician or a leading Labour member where the lines are blurred and everything is up for grabs. And as for Greg lake, well it was always an anti-Christmas song, and this year it seems we are definitely getting the Christmas we deserve.

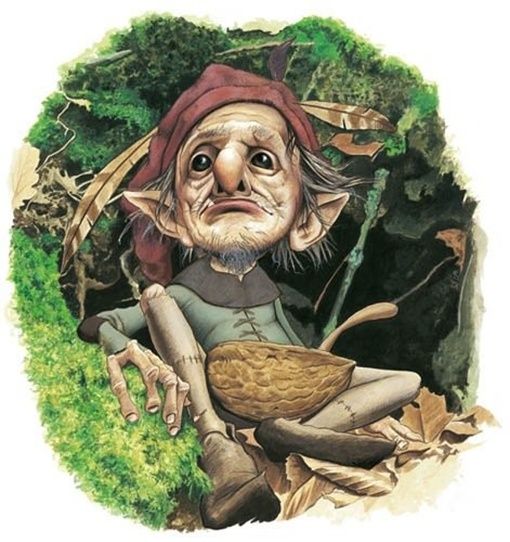

In the older and less frequented parts of the forest here in Huelgoat the seasonal hover between life and death seems less evident. Despite the loss of leaves, there is an unexpected depth of green and a darkness that can still envelop the late walker (after 3 O’Clock in the afternoon). The tree trunks are covered to their tops with lichen, a mossy coat that gives them a warm-blooded appearance, at odds with the decay going on around them as winter progresses. Pressing a hand on the trunk fills one with a sense of the animal vitality of trees – borne out by their ability to communicate and their ceaseless chatter amongst themselves. Fir trees swell the ranks of the ancient deciduous woodland, clamouring together, often planted as quick growing timber, shutting light from the forest floor and knitting their branches into dark passages. There is still so much to see, hear and to smell, that rich scent of leaf mould, of decaying bracken and wet moss. Later varieties of fungi are still poking their caps out above the top layer of leaves, to enjoy their brief moment of youth before a rapid evolution and reproductive cycle turns them into shrivelled and warty masses.

In the older and less frequented parts of the forest here in Huelgoat the seasonal hover between life and death seems less evident. Despite the loss of leaves, there is an unexpected depth of green and a darkness that can still envelop the late walker (after 3 O’Clock in the afternoon). The tree trunks are covered to their tops with lichen, a mossy coat that gives them a warm-blooded appearance, at odds with the decay going on around them as winter progresses. Pressing a hand on the trunk fills one with a sense of the animal vitality of trees – borne out by their ability to communicate and their ceaseless chatter amongst themselves. Fir trees swell the ranks of the ancient deciduous woodland, clamouring together, often planted as quick growing timber, shutting light from the forest floor and knitting their branches into dark passages. There is still so much to see, hear and to smell, that rich scent of leaf mould, of decaying bracken and wet moss. Later varieties of fungi are still poking their caps out above the top layer of leaves, to enjoy their brief moment of youth before a rapid evolution and reproductive cycle turns them into shrivelled and warty masses.

Herbert’s unique story has now been told in a book

Herbert’s unique story has now been told in a book  My book, Shell Shocked Britain, was published by

My book, Shell Shocked Britain, was published by

As is usually the case when I get to writing, I hunt down a poem I enjoy with at least a link to the subject I am working on. It is a strategy that has introduced me to work I wouldn’t otherwise have discovered, and today that is definitely the case. Pablo Neruda was once a great favourite of mine, but he and I have been strangers for a while and this is one I had forgotten, or hadn’t read.

As is usually the case when I get to writing, I hunt down a poem I enjoy with at least a link to the subject I am working on. It is a strategy that has introduced me to work I wouldn’t otherwise have discovered, and today that is definitely the case. Pablo Neruda was once a great favourite of mine, but he and I have been strangers for a while and this is one I had forgotten, or hadn’t read.

I have written two posts on this blog marking Keats’s death. The first was

I have written two posts on this blog marking Keats’s death. The first was