John Keats has been viewed by many as the very picture of the romantic poet, destined to die poor and at a young age. He was a man who attracted a devoted group of friends who in many ways promoted that image after his death, at the age of 25, from tuberculosis. Disgusted at the treatment he received from prominent literary critics of the early 19th century some suggested that his constitution had been weakened by these attacks; Shelley wrote the poem Adonais, portraying Keats as victim; Byron, hugely popular at the time and disliked by Keats wrote disparagingly of him as ‘snuffed out by an article’ and later in the 19th century Oscar Wilde still spoke of him as a martyr. Thus the perception of Keats as the archetypal frail, sensitive poet became enshrined in 19th and early 20th century consciousness.

However, we have written descriptions of him offered by a number of friends and acquaintances in the ‘Keats Circle’ and not one of them suggests frailty or weakness. Poet, critic and friend Leigh Hunt described him as having features ‘at once strongly cut and delicately alive’ suggesting his one fault was ‘in the mouth, which was not without something of a character of pugnacity’. The poet Barry Cornwall (real name Bryan Procter) claimed he had ‘never met a more manly and simple young man.’ Charles Brown, a close friend, described him as ‘though thin, rather muscular’. He had brown hair and hazel eyes and a ‘peculiarly dauntless expression’, Joseph Severn noted, all ‘trembling eagerness’. Others suggested he had an ‘inward’ contemplative look. He was undoubtedly a beautiful young man, but as his biographer Andrew Motion points out the descriptions are always of one ‘at once ‘feminine’ and robust’. Motion has been one of the most recent to write of Keats as a radical, both in politics and in poetry and at last the myth of ‘poor Johnny Keats’ is being erased.

John Keats was born in 1795, the son of the manager of the Swan & Hoop stables and inn, Moorgate, now on the main route into the City of London. He was short and stocky and likened to a boxer; indeed as a child at school he was well known as having a quick temper and always ready to fight his, or another boy’s corner. As an adult he was intense and acutely sensitive and alive to the world around him and his poetry is some of the most sensuous in the English language. Yet for all his ability to literally take you ‘out of this world’ he was not, as some believed ‘unworldly’ and incapable of coping with the barbs thrown at him by the press. He had trained as a doctor at Guy’s Hospital when surgery was in its infancy and savage to a degree we can barely imagine and having given up medicine for poetry he then nursed his younger brother Tom, who was dying of TB, without help. He was loyal and selfless as a friend and was reported to have a great ‘sense of fun’. Clearly, the words of important contemporaries and subsequent eminent Victorians played a large part in perpetuating the myth of the weak and over-sensitive doomed youth, but perhaps posthumous artistic images of him played some part too.

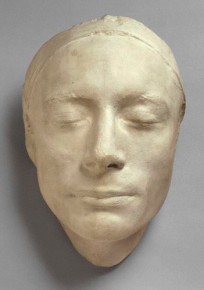

There are many likenesses and portraits of John Keats, taken whilst he was alive and painted posthumously, often with reference to each other. The life mask (Fig.1) was taken by the artist Benjamin Robert Haydon in 1816. His younger sister Fanny was particularly fond of this as a likeness, although she thought it had lost something around the mouth; his top lip naturally protruded over the bottom. Fig. 2 is one of the most famous portraits of the poet, a miniature painted by Joseph Severn in 1818 and by way of contrast, the charcoal drawing on the left (above) is also by Severn and for me is a far more lively portrayal; more representative of the written descriptions of him. Fig. 4 is a pencil drawing by Charles Brown from 1819, the year in which much of Keats’ greatest poetry was written, but just eighteen months before he died. It seems natural and unforced but so different again that the man that is Keats is ever more blurred.

This last sketch is of Keats on his deathbed (Fig. 5) drawn by Severn to ‘keep me awake’ as he nursed Keats in his final days in Rome in February 1821. This is a tragic portrait. Keats suffered terribly in those last months. He knew he was dying and that there was no hope of recovery but friends supported the doctor’s advice that a winter abroad would give him back his health. So he felt he had to travel with Severn, not a close friend but the only one willing and available, to Italy, away from Fanny Brawne the woman he was passionately in love with and secretly engaged to. He showed anger and bitterness and endured agonies that shocked and frightened Severn. This may be one of the reasons why, following Keats death in February 1821, Severn used his talents as an artist to recreate the sensitive, golden youth; the talented young poet that he preferred to remember and thus this exercise in imagination ensured that representations became more saccharine and anodyne.

Fig. 6 to the left was started by Severn in 1821 and finished in 1823. It is a recreation of Keats in one of his favourite poses, reading in his sitting room in Wentworth Place in Hampstead. Similarly, the next is Severn again, imagining Keats listening to the famous nightingale of his Ode to a Nightingale on Hampstead Heath. For me it bears little resemblance to the portraits above and shares nothing of their liveliness. The painting is a fiction, painted twenty years after his death, and for me a dull one.

Then there is the portrait (Fig.8) that I fell in love with as a girl of twelve and which was for many years my ‘photo’ of Keats. I learned later that it was painted around 1822 by William Hilton ‘after’ the miniature of 1818 by Severn shown above. I prefer it, but it most certainly is not the ‘real’ Keats.

I do not have a detailed knowledge of art or art history, but my sense is that the ‘essence’ of Keats was as hard to capture in paint, charcoal or clay as it was, and still is, to describe accurately in words. During his lifetime the images vary greatly and after his death they take on the status of memorials, romanticized and although on the surface a ‘likeness’ they are in fact as unreal as the perception of him promoted alongside his poetry for the best part of 150 years after his death.

One of the most recent portrayals of Keats is the small statue by sculptor Stuart Williamson at Guy’s Hospital in London unveiled by Andrew Motion in 2007. Stuart Williamson himself suggested it was time to represent Keats as the robust and radical man he was, rather than the passive, sensitive type as he has frequently been represented. I have to say to my untrained eye it is a man older than twenty, but it is important that such a statue to him, by an eminent sculptor such as Mr Williamson, exists.

And last, but by no means least, is the depiction of Keats presented in the 2009 film ‘Bright Star’ directed by Jane Campion. It focuses on Fanny Brawne and her love for Keats, played by Ben Wishaw. It is a wonderful film, and there is no doubt that the actor will, for many, ‘become’ Keats, as the William Hilton portrait became Keats for me. But lovely as Ben Wishaw is, and brilliantly though he played Keats, he provided only yet another version of a reality that has proved impossible for others to accurately bring to life.

Perhaps that ‘reality’ should then be provided by Keats’ poetry and letters. I hope that over the course of the next few posts they will explain more eloquently why he is still read avidly by students today and why he is taking his place as one of the greatest poets in the English language alongside Milton and Shakespeare, both of whom he greatly admired and who most influenced him.

For more detailed background information please click on the links in the text above.

A very informative and beautifully written post Suzie. You obviously wrote it with feeling.

Certainly did! Thank you for your nice comment 🙂

Hello, I was led to our blog by way of a Google alert. I’m never sure if I have a favorite poet, but Keats is certainly in the top five, odd though it is to talk about poets as though they are rock musicians. Then again, why not? Many were the rock stars of their day.

I came to Keats later than you, by way of a Romanticism class I took as an undergraduate. I immediately read Walter Jackson Bate’s biography, which is still my favorite, and the letters. In graduate school, I took my masters qualifying exam on Keats.

I agree that Bright Star is a wonderful movie. A number of Romanticists have disparaged Campion’s interpretation of Keats’s life and work. I couldn’t disagree more. First, they forget that the film is from FB’s point of view, not Keats’s. Second, they fail to recall that Campion is herself an artist. Bright Star is not a “biopic” but something richer, I believe: an attempt to offer a glimpse of Keats and his poetry through the eyes of those who loved him. If we had FB’s letters, that portrait would no doubt be different. Campion fell in love with Keats herself, and that naturally inflects her interpretation.

I’m sorry to ramble on, but I do want to comment on the possibility that Keats suffered from bi-polar illness. I’m not myself persuaded by the evidence, in part because I have a resistance to the pathologizing of art. Of course, I don’t mean to imply that is what you’re doing! I didn’t read your post that way at all. I’m just explaining why I’m not receptive to that interpretation of his moods. I also tend to think that mental illness is in part historically contingent. In other words, certain behaviors are regarded in a positive or negative light based on how adaptive they are to the circumstances of the age. There is quite an interesting book on the topic of bi-polar illness and creativity: Kay Redfield Jamison’s _Touched with Fire: Manic Depressive Illness and the Artistic Temperament._ I don’t recall whether Jamison mentions Keats. I don’t always agree with her, but Jamison is a wonderful and sensitive writer.

I’m going to bookmark your blog.

Annie

Thank you so much for taking the time to comment Annie. I am really interested to hear your views. I totally agree with you about Bright Star and I for one was relieved when Jane Campion gave us Fanny’s point of view. It is notoriously difficult to film a traditional biopic in a way that satisfies.

I will definitely look up Kay Redfield Jamison’s book as it is an area of creativity that I find fascinating whether or not a posthumous diagnosis can be made. When I write these blog posts about Keats I am approaching them from the perspective of an enthusiastic amateur scholar and I am sure much is simply my emotional response to what I read of his life and work. No other poet has touched me in quite the same way, although I do have many other ‘favourites’ mainly from the 20th century. I studied law at Uni and have always regretted not taking Eng Lit. Walter Jackson Bate is one of the biographies I most enjoyed too because for me he combined life and literature very successfully.

Anyway, I am going on a bit. I hope you will comment on my blog again in the future. I cover topics other than Keats and hope there is always something to interest you. Thanks for your interest. Suzie

P.S. In my first sentence, “our” should obviously be “your.” I’m chalking this up to a Freudian slip.

An excellent post as usual, Suzie – your enthusiasm shows through so strongly. My favourite, even though it’s the most morbid, is Severn’s death bed drawing, which is unbearably moving. I haven’t yet seen the film precisely because I don’t want the film-maker’s interpretation, however good, getting in the way.

Yes, that one is tragic. I feel for Severn too when I see it as he was truly shocked at the manner of Keats’ death.

Bright Star is a fabulous film but once seen it is hard to visualise the characters in any other way than portrayed on screen. For me this affects my picture of Fanny more than Keats though.

hello. I am very fond of Keats and loved the film, but I doubt if any representation will do justice to what he really looked like. The .first time I remember reading a character description of him, in a book by Frank Muir, he certainly didn’t appear to be a poor pathetic creature with his head in the stars. I like the thought of him getting into fights and being a good friend, fond of a laugh …there was no cure found for TB until the 20th century so he was one of the unlucky ones. I am surprised Joseph Severn managed to escape the disease, what with his devoted nursing of Keats in Rome. I Llike reading his letters to his friends and family, and I have a sort of idea in my head of the sort of man he was. handsome, very kind and a good friend !

ps i should say that I live on the Isle of WIght, (UK) where Keats stayed twice – in 1817 and 1819 (I think). On the wall by the main entrance of our one and only hospital are the opening lines of Endymion…. a small local connection!

There was also a massive TB hospital on the south side of the Island, opened 1864, closed 1964 and demolished in 1969. The only thing available was fresh air, rest and something called collapse therapy…until the advent of drugs.

You have the same view of his as I do – a young man of amazing generosity to his friends – of both spirit and and with money he actually needed himself. Most descriptions of him stress his lively expression and he does sound very attractive. I like the thought that his sister felt the life mask represented his true appearance best. Full of ‘life’ is how I always prefer to imagine him.

if anybody is interested after all this time! last February I actually went to Keats House in Hampstead, and had a wonderful tour of the house by a lady volunteer, who was quite plainly in love with him. I can’t say I blame her, either. Also went along Well Walk, where Keats lived with his brothers, and where Tom died. The original house has gone (I think?) but it’s nice to imagine of them enjoying each other’s company, for a short time, at least.

He is so easy to love! There is something so moving about his life, let alone the power of his poetry. I do think it is his letters that have given many that additional insight into the human being behind the myth of the romantic poet. Hampstead is such a wonderful place. I could go when i liked before I moved away from London. But it is so very worth the trip, as you so clearly found. Thanks for commenting again!

well, i love him so much i am going again today 🙂 I am staying in London at the moment on my own (a bit daunting, to be honest) but I still have a free ticket from last February. What do you think about that new book? I must have a read! I got the impression he was a real ‘man’ from Andrew Motion’s book…I loved the film, but the portrayal seemed a bit wishy-washy for my liking. He was the sort of fellow, that if he lived nowadays, would be the centre of attention in the pub, a good story-teller – and all the ladies would love him 🙂 I don’t like the thought of him being addicted to alcohol and drugs (laudanum), and possibly sex, but this was the 1800s and it was very much a male-dominated society. It’s strange to think that if we were alive today we probably wouldn’t have been able to socialise with him and his friends, unless we were chaperoned or very high society…some things have changed for the better, I reckon!

oops…I meant: if we were alive then, of course. xx

How lovely to be going again! Where have you been staying? I am in London in a three weeks time for book research but am staying miles away and training in – it takes too long from Taunton for a day trip.

Nicholas Roe’s book is getting a lot of publicity precisely because of the sex and drugs and rock n roll aspects I think. Andrew Motion has said something interesting – that Nicholas Roe is making assumptions just like he had to make assumptions and really there is little evidence of addiction to either sex or opium from his letters. His relationship with Fanny wasn’t sex-obsessed, just obsessed, and that has always been thought a common symptom of consumption. But Nicholas Roe is a brilliant Keats scholar who worked hard to dispel; the myth of Keats as a man apart from the world around him and identified him as a radical poet so it has opened an interesting debate.

We would have been unlikely to be included in the late night talking and drinking sessions that Keats and his friends enjoyed – you’re right! Mind you, some women were accepted and taken seriously – I should like to have been Mary Wollstonecraft for example 🙂

i am staying near Alexandra Palace –a very nice place and close to the bus stops and trains into the city. I went yesterday to Keats House, in the pouring rain and howling gales, ha ha! there’s devotion for you. I was the first one in the house too, I arrived at the gates just as the lady opened them. I also took some photos of Well Walk, and found Pond Street, where he used to get the coach to and from town. I wonder if he ever cursed the weather as he waited for the ‘bus’ Anyway, as you said there was no hint of drugs or sex in the letters (maybe desire and frustration), and he may have got addicted to laudanum in his last few months, but that is hardly surprising. I don’t know if he ever wrote openly about any sexual relations with, say, prostitutes, to his close friends or his brothers, but I certainly didn’t get the impression of him being especially driven in that direction. I have read James Boswell’s London Journal (1762-3)…I know that wasn’t meant for public consumption (or was it?), but he certainly didn’t hold back in describing his exploits. (I would recommend a read, it’s such a good book. What I liked about it, apart from the snapshot of life in the 1700s, was the way Boswell could laugh at himself. He was a snob and a lech though, no doubt.) I would sort of expect Keats to have the almost same honesty, but we haven’t seen anything, as far as I know. He might well have caught something unpleasant at one time or another but again, that wasn’t unusual either, in those days. I think Andrew Motion’s book is excellent-he made Keats into a real man, and made me want to find out more about him.

I agree – it is Andrew Motion for me as far as biographies go. You must give me the name of the place you are staying in – is it a b&b? I always struggle to find somewhere reasonable and comfortable in London. I understand your devotion! I am sure Keats endured many uncomfortable journeys by coach – it was a very different environment too – much more like a village of course. You have really made me want to get up there again!

well i’m very fortunate, i am staying in a relative’s place while they are off sunning themselves abroad 🙂 i wouldn’t know where to stay myself, otherwise. I am getting very handy with the buses and tubes, although I don’t like the underground (who does, honestly?) Tomorrow I am off to Highgate, I went through it the other day on my way to dear Keats, it’s not far on the bus. Plus I don’t think it will be raining. On Friday it’s back to the isle of wight: all good things come to an end. I’m glad I went to Hampstead again: it won’t be the last time !